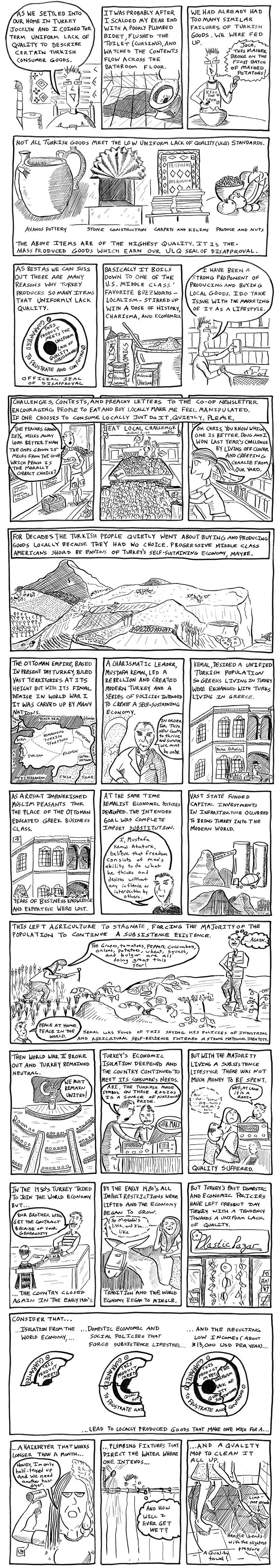

Uniform Lack Of Quality

Jocelyn and I both really like the term Uniform Lack of Quality. Instead of fighting (as we do about most things) over who got to use it in his or her writing or drawing we decided to approach the topic separately, without any specific discussion about what each of us would create. Both of us knew the general direction of each post but not the specifics. The results are what you read above and below.

“Uniform Lack of Quality”

We moved into our house in Duluth nearly seven years ago and immediately began ruing the choices of the previous owners. There was the orange shag carpet covering the entire main floor. There was the peel-and-stick faux tile they’d laid in the kitchen, stuff that would grab on to the bottom of a bare foot and become a temporary flip-flop. But what really irked us was the bathroom.

Here’s a little life lesson that’s only really sunk in for me in the last 15 years: you get what you pay for.

With bathrooms, as with shoes, it’s worth shelling out for quality rather than congratulating oneself for saving money and then ending up with a cheap toilet that grabs on to one’s buttocks and becomes a temporary tushie flip-flop.

I mean, speaking of toilets and shoes or whatever.

In our Duluth house, the first year was spent dealing with a toilet that clogged with the faintest trickle of urine; with a tub that drained so slowly we wondered if Yanni had left off playing at The Acropolis in order to depilate in our shower; with a sink that dripped with the predictable constancy of Homer’s Penelope.

With each repair that we made, we moaned about the cheapskate previous owners, sometimes summoning their ghosts by holding a Ouija board up to the cracked medicine cabinet mirror and laboriously spelling out, “W-O-U-L-D I-T H-A-V-E T-A-X-E-D Y-O-U O-V-E-R-M-U-C-H T-O S-P-E-N-D F-I-V-E M-O-R-E D-O-L-L-A-R-S O-N A P-R-O-D-U-C-T T-H-A-T A-C-T-U-A-L-L-Y C-A-M-E I-N A B-O-X W-I-T-H A R-E-C-O-G-N-I-Z-A-B-L-E B-R-A-N-D N-A-M-E O-N I-T?”

Then–replaying current history here–we made the choice to leave behind the small woes of our Duluth lives and hie off for some adventurous months that would be chock full of New, of Special, of Not My Problem.

We call that choice Turkey.

Unfortunately, we undermined the “leaving behind small woes” part of the choice by renting a house in Turkey.

Turkey is a country that falls on the Continuum of Development at a point called We Have Not Great Amounts of Money and We Love Plastic. A similar attitude can be seen in Central American countries, where an agricultural tradition has rubbed up against an industrial world, where people working with their hands have seen that life is immensely easier when there’s an indestructible plastic bucket in the kitchen rather than a breakable clay pot. All the better if that plastic bucket is bright pink.

What’s more, because of where it is in terms of development, Turkey’s workaday Allah is the plastic bag. Seen blowing across the countryside, wadded up in the trunks of cars, tied onto bicycles as flags, lazing around trash-strewn ruins, breezing out of every shop (even if one has merely purchased a pack of gum), plastic bags are both worshiped and ubiquitous—the perfect complement to all those pink plastic tubs, in fact. Tubs & Bags are like Flatt & Scruggs, creating an aura of banjo music for all the Jethros, Ellie Maes, Mustafas, and Hayriyes twanging around the hillsides.

Despite its many uses, plastic doesn’t elevate the tone of a place or, ultimately, actually make life better.

The New Testament delineates it quite clearly: “Thus crap begat plastic, and plastic begat trash, and trash begat junk, and junk begat headaches.”

It turns out this line is the same in both the King James and the Qur’an. Junk gave us trouble back in our Duluth house; junk gives us headaches in our Ortahisar house. The upshot is that crap plastic trash junk, in its global applications, does not make for low-maintenance homes.

As it turns out, though, the cheap junk in our Ortahisar house completely trumps the cheap junk in our Duluth house.

Mostly because there’s this thing in Turkey named Every Last Bit of Our Plumbing Is Plastic.

As in, the pipes used to transport water to a sink, to evacuate a toilet, to drain a shower…are PVC.

Compounding this is the fact that the toilets in our house aren’t actually attached to the floor, even though they have holes where screws could go. Unattached, the porcelain is easier to move–so that when a significant leak runs out the back of the toilet and across the bathroom floor, the repair is straightforward. A person just tips the toilet forward, which then exposes the plastic pipes that need fixing. This is not unlike what one would see beneath a toilet in The States, but in The States there’s also a wax ring sealing off potential leakages. In The States, the toilet is moored to the floor so that the movements of users don’t cause the plastic pipes to crack. Not so in Turkey. Here, the toilet moves with every wipe-related lean, which, in turn, stresses the plastic pipes, which, thereafter, crack and release smelly runoffs. Most likely, the toilet isn’t screwed to the floor because the floors are made out of cement or stone, and it’s hard to drill a screw into cement or stone…

you know

unless you have the right drill bit.

Which is to say don’t get me started.

On the positive side, though, a constant breakdown of fundamentals in one’s household does create situational language lessons. By this, I mean that Groom had to learn how to say “I’d like to buy a hammer, please” mere weeks off the plane. This was before he knew how to say “Nice to meet you” or “That looks suspicious; will it make me ill?”

However, soon after we rented the old Greek house in Ortahisar, Groom tired of language immersion school in the hardware store. He hated spending several hours each day looking up vocabulary, walking around town, taking apart and reassembling bits of the bathroom. Even worse was when we’d report the problem to our landlord, who, quite responsively, would avow, “I’ll send my friend over. He’ll fix it.” The thing about Friend is that he’s the one who designed and installed the bathroom; he thinks the place is pretty nifty and that we should stop abusing the place through frequent urination. If we hydrated less, the bathroom would remain infinitely more intact.

Startlingly quickly, the exhaustion created by Plastic Failure and I’ll Send My Friend Over eroded our will into a preference for endurance over action. For example, we no longer expect hot water from the sinks…or necessarily out of the shower. When the kitchen sink started acting up, we had no problem shrugging and accepting, “Well, turning one of the handles still makes water come out. That’s good. Two handles are overrated. Let’s just leave that one valve stripped or blocked or whatever. If we fix it, we’ll just have to fix it again next month. At this point, it’s already habit to drop our brightly-colored plastic tub into the sink, fill up the little kettle on the counter to heat water, and do the washing up that way.” We don’t even blink anymore at what a time and energy suck it is—because there are no traps in the drains—that the kitchen sink is constantly clogged. We have a little teaspoon that fits just perfectly through the holes in the drain, so we do some poking around to dislodge bits of lettuce, and, with only a few minutes out of each hour devoted to the task, the trickle of cold water is draining again, just fine.

In this way, we have become Turkish. We look at the plastic, watch it founder, and shrug. Then we drink tea.

Our brains remain American, though. Even as I’m taking showers that veer from frigid to burning, my brain is pushing for an answer to the pounding question of why, why, WHY: “What in Smyrna is going on here? How can we be on a chunk of land that is one of the most inhabited places on the planet—that has had civilization after civilization come through—that had Romans, those masters of bathing and plumbing, on it two thousand years ago—that was ruled by the refined Ottomans—that seems as though it might have benefitted from all the layers of peoples and ideas—that seems as though it would have discovered copper (or some sort of hygienic) piping for the ‘potable’ water? What is going on here?”

Then I learned from a local anthropologist that the late-arriving inhabitants of Cappadocia (the Turks showed up maybe a thousand years ago and are, in some ways, still radically Middle Aged) had little means of benefitting from those who came before. According to him, the Turks who currently populate the landscape swooped down from Turkmenistan and discovered towns like Goreme, with all its cave homes and fairy chimneys, sitting abandoned. With the option of free housing in front of them, they discarded their nomadic lifestyles and settled in. Once I learned this tidbit, I started postulating that what we’re seeing now is the result of nomads settling; if a population’s cultural traditions are based around constant movement and not investing in a place permanently, then maybe they lack the context to question plastic household infrastructures.

Naturally, an easy answer can never be the whole answer.

Not soon after we started musing about the consequences of long-term wanderers settling down, we also started realizing that the issue of poor plumbing runs deeper than people on the backs of animals dismounting and cracking their backs with relief. Even further, we started realizing that we constantly see things analogous to poor plumbing, but in different areas of life. Grocery stores, too, feel like a riddle. Why, no matter the store or city, can we predict the products that will be for sale? Why does every store have exactly the same fourteen kinds of cracker, and why are none of these crackers actually very tasty? And on the roads: why does everyone drive rinky-dink tin can white Renaults? And why does every scrub brush’s handle snap off the first time I try to clean a plate?

Why, in this country of beauty and amazing architecture and admirable tolerance and consistently kind souls, is there so little variety in products, and why are the available choices so crappy?

Consulting each other in the befuddled manner common to couples in their second decade, Groom and I agreed it had to be more than a function of nomads deciding they wanted addresses.

The best explanation we’ve found so far is, indeed, historical—but more recent. To avoid writing a textbook on Turkish history (which would be even more riddled with errors than my descriptions of plumbing), I’ll condense things into a broad overview: Turkey sided with the Germans in World War I; that didn’t go so well, and after the war, Turkey became part of the spoils of victory, which meant that it was divided up amongst the victors; the Turkish people didn’t dig this action, and therefore they were delighted when a charismatic visionary named Mustafa Kemal (later renamed Ataturk, Father of the Turks) grabbed at power on the basis of reunifying and restoring his country. After Ataturk worked to modernize and secularize Turkey in the 1920s and 1930s, he wasn’t about to take any risks when World War II reared up, and so he kept Turkey out of the thing, opting instead to keep Turkey neutral and isolationist. A major side effect of this decision, coupled with worldwide shortages, was that Turkey came into its Industrial Age relying solely on homegrown factories and products. While such times can drum up new kinds of ingenuity, another reality is that such times also ask people who don’t really know what they’re doing to do things nevertheless, which begets limited and inferior products, which begets a citizenry that doesn’t know how to expect more, which begets a place that is perfectly satisfied with fourteen kinds of tasteless crackers and toilets floating around the bathroom.

If I could go back in time and have a sit down with Our Man Ataturk, I might–in addition to congratulating him for his hard-won republic–counsel him that, no matter what he feels he has to do during World War II, he should consider bringing in scientists, designers, and manufacturers from, say, Germany in the 1950’s. I wouldn’t ask him to turn over the running of Turkish companies, oh no. But I would urge him to allow them to do some training and consulting, particularly in the realms of home construction and mass production.

Unfortunately, my time machine ran out of AAA batteries last week, so it’s up on blocks for the present (if, in fact, there even is such a thing…). Drat. Now I can’t have that chat with Ataturk. Consequently, Groom and I will continue to marvel at all the shoddy quality, most notably in the awe-inspiring bit of magic that Turkish workmen conjured when they plumbed our Ortahisaran toilet and bidet. Somehow, in a way that defies all logic but could potentially be remedied with the installation of a one-way valve, they rigged things up so that the water in the shower is often cold, yet the water in the toilet is often near boiling.

Hence, and with significantly less tragedy than the Greek/Turkish population exchanges of the 1920’s,

if a toilet user hasn’t been paying attention to the queer warmth of the porcelain that day and, unthinkingly, turns on the bidet for a quick cleanse,

it brings on the most unexpected language lesson of all, a chance to shout out with great force and conviction:

“Tuvalette çikan borusudan simsicak su çkiyior!” (The bidet is scalding my bunghole!)